THE DOCTOR'S BAG

the blog about the medicine and surgery of yesteryear

the blog about the medicine and surgery of yesteryear

Dr Keith Souter aka Clay More

[We are living through a difficult and worrying time as we are in the midst of a global pandemic of Covid-19. I have been called out of retirement to go back into medical practice to help out, so I was not intending doing a blog this month. However, this blog from 2015 may be of interest as we can empathise with how people lived through past epidemics and pandemics.]

Fevers of all sorts were a constant anxiety to both doctors and the public in the 19th century, just as they had been in every society for millennia. Many of them could rip through a community, causing disability, suffering and death. They were poorly understood, yet somehow doctors had to do the best they could.

Hippocrates and fevers

The great Hippocrates of Kos, (460-370 BC), left a vast amount of medical writings. Philologists have spent whole careers trying to workout which of the books that make up the Hippocratic Corpus were actually written by him. Of the seventy books that make up this collection it is currently thought that he wrote nineteen or twenty, the rest being based upon his teachings. Two of them are relevant to us in this section. They are entitled: Airs, Waters, Places and Epidemics.

In Airs, Waters, Places he tells budding physicians that they should make a study of the air and the climate, the water supply and the surrounding countryside, including plants, animals and people, in order to understand how the environment can cause illness.

Anatomical theatre of the Archiginnasio, Bologna, Italy - the statue of Hippocrates

In Epidemics, he gives us a remarkable series of cases in which he describes actual people suffering from the various feverish illnesses, complete with clinical descriptions and the path to recovery or death. He describes the physical changes that occur, the alteration in the appearance of the urine, bowel movements and the fluctuations in the fevers.

In this section from Epidemics, translated by Francis Adams in 1865? gives you the impression that you are listening to this ancient doctor recounting his rounds of his patients, staying in the different parts of a Greek city, complete with numerous temples to the gods:

In these diseases death generally happened on the sixth day, as

with Epaminondas, Silenus, and Philiscus the son of Antagoras. Those

who had parotid swellings experienced a crisis on the twentieth day,

but in all these cases the disease went off without coming to a suppuration,

and was turned upon the bladder.

But in Cratistonax, who lived by the temple of Hercules, and in the maid servant of

Scymnus the fuller, it turned to a suppuration, and they died. Those who had a crisis

on the seventh day, had an intermission of nine days, and a relapse

which came to a crisis on the fourth day from the return of the fever,

as was the case with Pantacles, who resided close by the temple of

Bacchus.

Those who had a crisis on the seventh day, after an interval

of six days had a relapse, from which they had a crisis on the seventh

day, as happened to Phanocritus, who was lodged with Gnathon the fuller.

During the winter, about the winter solstices, and until the equinox,

the ardent fevers and frenzies prevailed, and many died. The crisis,

however, changed, and happened to the greater number on the fifth

day from the commencement, left them for four days and relapsed; and

after the return, there was a crisis on the fifth day, making in all

fourteen days.

The crisis took place thus in the case of most children,

also in elder persons. Some had a crisis on the eleventh day, a relapse

on the fourteenth, a complete crisis on the twentieth; but certain

persons, who had a rigor about the twentieth, had a crisis on the

fortieth. The greater part had a rigor along with the original crisis,

and these had also a rigor about the crisis in the relapse. There

were fewest cases of rigor in the spring, more in summer, still more

in autumn, but by far the most in winter; then hemorrhages ceased.

Hippocrates divided fevers according to times when they peaked. Thus: quotidian (daily), tertian (peak every 3 days), quartan (peak every 4th day).

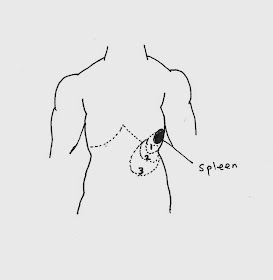

He also noted that those who lived in or near swamps or marshes and who drank stagnant water had large stiff spleens, a characteristic of the disease that he called swamp fever. This undoubtedly was malaria. Although he did not appreciate that it was spread by mosquitoes, it was a startlingly accurate description of the disease. We shall return to the spleen later in another post when we look at some of the fevers.

Fevers and Pest houses

As we saw in a previous blog post about The Fight against Infections, people realised that many diseases spread case by case. The manner in which they spread was not understood, but three things were thought to cause illnesses: drinking tainted water, breathing bad air or touching affected individuals. The concept of contagion developed, meaning spreading by touching.

Those illnesses that spread rapidly as epidemics were thought best to be contained. Thus leprosy was dealt with by making affected people live in leper colonies, kept away from non-infected people. Many societies used special pest houses to 'look after' people with all those diseases that produced fevers that they thought could be risky to the community.

The origin of the term is from pestilence, for these were pestilence houses. In the Old West many towns had pest houses. What a lot of people don't realise, however, is that they had their origin back in the Old Country. And so, let me take you back a few centuries.

Epidemics and pandemics

These are terms used to describe the rapid spread of an infectious illness. An epidemic is when a locality is affected, whereas a pandemic is when an epidemic spreads across countries and across continents.

Throughout history there have been some notable epidemics and pandemics:

The plague of Athens of 430 BC killed about a quarter of the population of the Greek city of Athens. The actual disease has been the subject of much debate among scholars for decades. It is not thought to have been plague, but may have been measles, typhoid fever, thus or one of the viral hemorrhagic fevers. We will never know for sure.

The plague of Justinian from 541-542 AD was the first recorded instance of bubonic plague. It affected the eastern Roman Empire and killed between 25 and 50 million people. It is said that it killed 5,000 people per day in Constantinople.

The Black Death of 1347-1353 was a pandemic that raged across Europe, killing between 75-200 million people. It began in Asia and was carried along the Silk Road to Constantinople where it spread along the merchant routes across Europe. In England it reduced the population by 50 per cent.

Epidemics recurred across Europe on a virtual five year cycle for the next few centuries.

The three types of plague

Bubonic plague - characterised by large swellings called buboes. These are lymph nodes that swell to a huge size in the axillae (armpits), neck and groins, and become matted. The victims also experience fever, headaches, nausea and vomiting. The mortality rate was about 30 per cent. This was the dominant type of illness during the Great Plague. It was spread from the bite of an infected black rat flea, now identified as the bacterium Yersinia pestis.

Pneumonic plague - this is when the lungs are involved to produce a severe pneumonia. The death rate for this was even higher.

Septicaemic plague - this occurred when the infection reaches the blood stream. The mortality rate in those days would be almost 100 per cent.

The treatments would have been well virtually ineffective. People, including children were encouraged to smoke. Buboes were bathed and had leeches attached to them to such out blood and lymph. Bleeding was also done, using any number of recommended bleeding points. According to the medical texts of the time, bleeding at different points could have different effects.

In 1625 Santorio Santorio, a friend of Galileo invented a thermometer, capable of assessing body temperature. With it he was able to show that people with so-called hot temperaments did not have raised temperatures. In a sense it was evidence against the Doctrine of Humours, but it no effect on medical practice because practitioners clung to the teachings of antiquity.

In physics various thermometers were developed by scientists who needed to measure the amount of heat that things could attain. Fahrenheit developed his temperature scale in 1704 and Celsius produced his in 1742. Doctors did not adopt them, for they found no need to put a figure on the temperature of the body. They continued to feel with their hand and pontificate from ancient dogma.

It was not really until Professor Carl Wunderlich (1815-1877), a German physician started researching patient temperatures with a clinical thermometer that doctors started to understand the importance of temperature.

He established that there was a normal body temperature, of 37 degrees Celsius or 98.4 degrees Fahrenheit. He established that the pattern of a fever was important diagnostically and prognostically (prognosis is the technique of making a prediction of the outcome of a disease). He actually thought that every infectious illness had its own characteristic fever pattern, which could differentiate one disease from another. This is not actually the case, but his use of temperature charts was accepted and became an established part of medical practice.

Fevers and Pest houses

As we saw in a previous blog post about The Fight against Infections, people realised that many diseases spread case by case. The manner in which they spread was not understood, but three things were thought to cause illnesses: drinking tainted water, breathing bad air or touching affected individuals. The concept of contagion developed, meaning spreading by touching.

Those illnesses that spread rapidly as epidemics were thought best to be contained. Thus leprosy was dealt with by making affected people live in leper colonies, kept away from non-infected people. Many societies used special pest houses to 'look after' people with all those diseases that produced fevers that they thought could be risky to the community.

The origin of the term is from pestilence, for these were pestilence houses. In the Old West many towns had pest houses. What a lot of people don't realise, however, is that they had their origin back in the Old Country. And so, let me take you back a few centuries.

Epidemics and pandemics

These are terms used to describe the rapid spread of an infectious illness. An epidemic is when a locality is affected, whereas a pandemic is when an epidemic spreads across countries and across continents.

Throughout history there have been some notable epidemics and pandemics:

The plague of Athens of 430 BC killed about a quarter of the population of the Greek city of Athens. The actual disease has been the subject of much debate among scholars for decades. It is not thought to have been plague, but may have been measles, typhoid fever, thus or one of the viral hemorrhagic fevers. We will never know for sure.

The plague of Justinian from 541-542 AD was the first recorded instance of bubonic plague. It affected the eastern Roman Empire and killed between 25 and 50 million people. It is said that it killed 5,000 people per day in Constantinople.

The Black Death of 1347-1353 was a pandemic that raged across Europe, killing between 75-200 million people. It began in Asia and was carried along the Silk Road to Constantinople where it spread along the merchant routes across Europe. In England it reduced the population by 50 per cent.

Bubonic plague victims, 1411

Epidemics recurred across Europe on a virtual five year cycle for the next few centuries.

The three types of plague

Bubonic plague - characterised by large swellings called buboes. These are lymph nodes that swell to a huge size in the axillae (armpits), neck and groins, and become matted. The victims also experience fever, headaches, nausea and vomiting. The mortality rate was about 30 per cent. This was the dominant type of illness during the Great Plague. It was spread from the bite of an infected black rat flea, now identified as the bacterium Yersinia pestis.

Pneumonic plague - this is when the lungs are involved to produce a severe pneumonia. The death rate for this was even higher.

Septicaemic plague - this occurred when the infection reaches the blood stream. The mortality rate in those days would be almost 100 per cent.

The treatments would have been well virtually ineffective. People, including children were encouraged to smoke. Buboes were bathed and had leeches attached to them to such out blood and lymph. Bleeding was also done, using any number of recommended bleeding points. According to the medical texts of the time, bleeding at different points could have different effects.

Points for blood-letting, Field book of wound medicine, 1517

According to the Doctrine of Humours, which we looked at in the post on Joseph Lister and Aseptic Surgery people of a hot temperament were thought to be most likely to contract plague, because they had larger skin pores. They having greater heat could easily be treated by bleeding, because blood was considered to be wet and hot. Thus bleeding was thought to reduce the bad humour causing the disease.

Treating the sick was an unenviable task, considering the high mortality rate. Doctors wore long leather gowns and gloves and wore make with long beaks, which contained a sponge soaked in vinegar.

London and the Great Plague

The Great Plague was the worst outbreak of actual plague since the Black Death. The earliest cases occurred in the spring of 1665 in the parish of St Giles-in-the-Fields, the spread rapidly through the city of London during an especially hot summer. Those who could afford to fled the city. This included King Charles II, parliament and the law courts, which moved to Oxford.

The Lord Mayor, Sir William Lawrence and his aldermen(town councillors) were left to enforce the orders of the king, to try to limit the spread of the disease. He issued the so-called lord Mayor's orders on 1st July 1665. These stated that examiners, watchmen and searchers had to be established for each parish. The examiners (who had no choice in being appointed, upon penalty of imprisonment, had to serve for a two month period) had to enquire and determine which houses had anyone who was sick in them. They informed the constable who would arrange to have the house boarded up to contain the residents.

Every infected household then had to have two watchmen one for the day and one for the night, whose duty was to ensure that no-one entered or left the house.

The searchers were women of the parish who had to search the bodies of anyone who died to determine what disease they died of, specifically the plague.

In an attempt to reduce the carriage of disease, men were appointed to kill cats, dogs, pigeons and rats, although the relationship of rats and rat fleas to the plague were unknown.

Public gatherings and funerals were not permitted. People dying from plague had to be buried in plague pits rather than in church graveyards between sundown and sunrise. Relatives were not allowed to hold a service at the grave.

In 1666 an important statute was passed entitled Orders for the prevention of Plague. This set down the law certain things that had to be done in every town and city in the land. It stated that every town had to provide a pest house (a pestilence house), consisting of a building, huts or sheds in readiness for any break out of infection. Thus was the pest house established in law. That law extended to the colonies and as such, over the centuries, the pest house became part of the culture. Originally intended as a place to care for and exclude plague victims, it became the infectious disease 'hospital' for communities.

The plague in literature

Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) was a Member of Parliament who famously kept a diary from 1660 -1690, which gives us a great insight into life during the Restoration period (the reign of King Charles II, or the restoration of the monarchy after the English Civil War of 1642-1651, when King Charles I was executed for tyranny).

Daniel Defoe, author of Journal of the Plague Year, published 1722

The thermometer - a vital clinical instrument

The Doctrine of Humours was, as I have mentioned before, the dominant theory in medicine for millennia. Doctors were aware that when people had fevers they felt hot to the touch, yet assessing this heat was totally subjective. A physician could postulate about a patient having a hot temperament and a hot illness, yet there was no way of demonstrating this.Treating the sick was an unenviable task, considering the high mortality rate. Doctors wore long leather gowns and gloves and wore make with long beaks, which contained a sponge soaked in vinegar.

London and the Great Plague

The Great Plague was the worst outbreak of actual plague since the Black Death. The earliest cases occurred in the spring of 1665 in the parish of St Giles-in-the-Fields, the spread rapidly through the city of London during an especially hot summer. Those who could afford to fled the city. This included King Charles II, parliament and the law courts, which moved to Oxford.

The Lord Mayor, Sir William Lawrence and his aldermen(town councillors) were left to enforce the orders of the king, to try to limit the spread of the disease. He issued the so-called lord Mayor's orders on 1st July 1665. These stated that examiners, watchmen and searchers had to be established for each parish. The examiners (who had no choice in being appointed, upon penalty of imprisonment, had to serve for a two month period) had to enquire and determine which houses had anyone who was sick in them. They informed the constable who would arrange to have the house boarded up to contain the residents.

Every infected household then had to have two watchmen one for the day and one for the night, whose duty was to ensure that no-one entered or left the house.

The searchers were women of the parish who had to search the bodies of anyone who died to determine what disease they died of, specifically the plague.

In an attempt to reduce the carriage of disease, men were appointed to kill cats, dogs, pigeons and rats, although the relationship of rats and rat fleas to the plague were unknown.

Public gatherings and funerals were not permitted. People dying from plague had to be buried in plague pits rather than in church graveyards between sundown and sunrise. Relatives were not allowed to hold a service at the grave.

In 1666 an important statute was passed entitled Orders for the prevention of Plague. This set down the law certain things that had to be done in every town and city in the land. It stated that every town had to provide a pest house (a pestilence house), consisting of a building, huts or sheds in readiness for any break out of infection. Thus was the pest house established in law. That law extended to the colonies and as such, over the centuries, the pest house became part of the culture. Originally intended as a place to care for and exclude plague victims, it became the infectious disease 'hospital' for communities.

The plague in literature

Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) was a Member of Parliament who famously kept a diary from 1660 -1690, which gives us a great insight into life during the Restoration period (the reign of King Charles II, or the restoration of the monarchy after the English Civil War of 1642-1651, when King Charles I was executed for tyranny).

Samuel Pepys the great diarist

From his diary entry for Wednesday, 16th August 1665:

"But, Lord! how sad a sight it is to see the streets empty of people, and very few upon the 'Change. Jealous of every door that one sees shut up, lest it should be the plague; and about us two shops in three, if not more, generally shut up."

Daniel Defoe (1660-1731), was a journalist, novelist and pamphleteer and spy, who penned such famous novels as Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders. In 1772 he wrote a novel entitled Journal of the Plague Year.

In the novel he tells of how between 18 and 20 watchmen were killed as people attempted to escape from plague houses.

Not far from the same place they blew up a watchman with gunpowder, and burned the poor fellow dreadfully; and while he made hideous cries, and nobody would venture to come near to help him, the whole family that were able to stir got out at the windows one storey high, two that were left sick calling out for help. Care was taken to give them nurses to look after them, but the persons fled were never found, till after the plague was abated they returned; but as nothing could be proved, so nothing could be done to them.

Site of a City Pesthouse of London, used in the Great Plague

In 1625 Santorio Santorio, a friend of Galileo invented a thermometer, capable of assessing body temperature. With it he was able to show that people with so-called hot temperaments did not have raised temperatures. In a sense it was evidence against the Doctrine of Humours, but it no effect on medical practice because practitioners clung to the teachings of antiquity.

In physics various thermometers were developed by scientists who needed to measure the amount of heat that things could attain. Fahrenheit developed his temperature scale in 1704 and Celsius produced his in 1742. Doctors did not adopt them, for they found no need to put a figure on the temperature of the body. They continued to feel with their hand and pontificate from ancient dogma.

It was not really until Professor Carl Wunderlich (1815-1877), a German physician started researching patient temperatures with a clinical thermometer that doctors started to understand the importance of temperature.

Dr Carl Wanderlich introduced the thermometer into clinical practice

He established that there was a normal body temperature, of 37 degrees Celsius or 98.4 degrees Fahrenheit. He established that the pattern of a fever was important diagnostically and prognostically (prognosis is the technique of making a prediction of the outcome of a disease). He actually thought that every infectious illness had its own characteristic fever pattern, which could differentiate one disease from another. This is not actually the case, but his use of temperature charts was accepted and became an established part of medical practice.

Malaria and the clue to pain relief

In the mid-seventeenth century, powdered Peruvian Bark – known as chinchona – was extolled for its properties in the treatment of malaria and other fevers. The problem was that Peruvian Bark was expensive.

A chance discovery by the Reverend Edward Stone (1702–68) an English clergyman in 1763, that powdered willow bark tasted like quinine, led him to use it as a substitute for chinchona bark.

To his delight and amazement, it seemed to have a range of activity beyond that of chinchona’s ability to reduce fevers. Most significantly, it also had pain-relieving qualities. Crucially for the scientific community, he wrote about his discovery in a letter to the Royal Society, who published it in their Philosophical transactions in 1763.

I treated five and forty of my parishioners who were suffering from various agues [fevers] with increasing doses of powdered willow bark … and almost all of them rapidly improved.

Significantly, Reverend Stone referred to the Doctrine of Signatures as being the reason that he was drawn to test willow bark. Although he does not say so, it is likely that he had been aware that willow preparations had been used in local folk medicine.

Aspirin the wonder drug

Throughout the mid-eighteenth century, doctors prescribed salicin and salicylic acid with good results for many painful conditions, including arthritis, gout, rheumatic fever and typhoid fever. Unfortunately, they also found that many people suffered from significant bleeding problems, gastric irritation and stomach ulceration. There was a need to find a less troublesome treatment.

The major breakthrough came in 1897, the German chemist Felix Hoffman was working for the German pharmaceutical company Bayer. He was looking for a way to produce a form of salicylic acid that would not produce stomach irritation. There was a personal motivation behind this: his father had found salicylic acid effective, but also found the gastric side effects too hard to cope with.

Using the herb meadowsweet as the source for salicylic acid, Hoffman gave his father various modified forms of salicylic acid and eventually managed to produce acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) by using a different chemical process. The result was a form of acetylsalicylic acid that his father found worked extremely well.

In 1899, Bayer patented the method of preparation of aspirin and obtained the trademark for it as Aspirin. It is thought that the choice of name derived from ‘A’ for ‘acetyl’; ‘spir’ for Spiraea ulmaria (meadowsweet) and ‘in’ … which was simply a common ending for a drug.

In the 21st century we have learned much about this amazing drug - which certainly cannot be used by everyone, because it can have dangerous side effects for some people. Apart from being an antipyretic and analgesic drug, it is anti-inflamatory and seems to have protective effects against heart disease, stroke, many cancers and possibly even doe types of dementia. It is outside the scope of this book to say further, but fuller information about research is contained in the author's book An Aspirin a day.

***

If you want more Clay More!

My short story from Sundown Press

Twisted Knee, Ohio, 1866

Nothing could ever damp down the smell of the pest house.

Especially not in the sweltering heat of summer.

It was a strange, stomach-twisting smell that wafted from the two chimneys that belched smoke most days when the place was full of patients. And even when the smoke was dispelled by the wind the odor hung like a miasma around the old two-storied timber building a couple of hundred yards from the edge of the town of Twisted Knee.

But the smell was only a prelude to the evil that took place in the old building that housed the wounded, the diseased, and the hopeless. Though Doctor Cutler had his own faults, murder was not one of them—and that was going to be the death of him…

***

And if you want to know about Aspirin, this book as Clay's alter ego.....