THE DOCTOR'S BAG

the blog about the medicine and surgery of yesteryear

the blog about the medicine and surgery of yesteryear

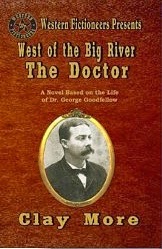

Dr Keith Souter aka Clay More

[We are living through a difficult and worrying time as we are in the midst of a global pandemic of Covid-19. I have been called out of retirement to go back into medical practice to help out, so I have not had time to write a new blog this month. So forgive me for posting this blog from 2014, which may be of some interest to my fellow writers.]

Tombstone, A.T, 1881

Just after Christmas, Marshal Virgil Earp was gunned down on Fifth Street, between the Oriental Saloon and the Golden Eagle Brewery. Three men blasted at him with shotguns from the cover of the adobe Huachuca Water Company building that was being erected. Virgil was badly wounded in the back and the upper left arm. It was clearly a reprisal shooting for the OK Coral gunfight, that had taken place in October.

Virgil Earp (1843-1905)

Doctor George Goodfellow was called to attend on him. His immediate assessment was that amputation of the arm would be needed, but Virgil steadfastly refused, saying that he wanted to go to his grave with two arms. And when he saw his wife, he told her not to worry, for he would still have one good arm to hug her with.

Dr George E. Goodfellow (1855-1910)

A brief history of amputation

The word amputation comes from the Latin amputare, meaning 'to cut away.' Surgical amputations were performed as far back as the days of Hippocrates, the father of medicine, in the 5th century BC. Amputation of limbs was performed due to battle injury or after severe accidents.

In the 16th century the French military surgeon Ambroise Pare introduced the technique of ligation of blood vessels instead of artery with hot irons. This dramatically reduced the torrential loss of blood that was often fatal.

Wilhelm Fabry, regarded as the father of German surgery was the first to emphasise the importance of amputating through healthy, rather than diseased tissue. He used cautery and also 'weapon salve'. This involved applying a salve to the weapon that caused the wound, not the weapon itself. It was based on 'sympathetic magic,' the belief that treating the blade that made the wound would cure the wound. Although it seems ridiculous to us, yet he achieved surprisingly good results, or at least results better than those surgeons who applied medication to the wounds after they had operated. The reason of course is that he wasn't putting poisons and further bacteria into the wounds.

In 1674 the tourniquet was introduced, which allowed surgeons more time, and gave them the opportunity to work in a relatively bloodless field. This is of inestimable value, since surgeons could identify anatomical structures more accurately.

To operate or not

Surgeons were of great value in wars, yet the experience of the British surgeons during the Crimea War (1853-1856) brought up the question of whether it was better to operate or not. That is, whether to adopt a conservative approach, or the dramatic one of surgery. The infection rate was extremely high as was the mortality rate after amputation. The British Surgeon General Guthrie advised against amputation except where the limb had been struck by a cannon ball. Nonetheless, individual surgeons operated and removed limbs when bones had been shattered by the Minie ball, the bullet that was to prove so effective in the Crimea and in the Civil War.

During the Civil War Dr D.D. Slade wrote a pamphlet that encouraged the orthodox view that amputation should be done immediately where there was great laceration of skin, or where there was a compound fracture (bone protruding through the skin), with splintering of the bone.

The germ theory had not been propounded at that time, so surgeons themselves often introduced infections. Instruments may have been merely wiped or washed, but not adequately sterilised (for there was not thought to be any necessity to do so). Added to this there was the problem of operating on men who may have been weakened by stress, disease or scurvy.

The Army position changed several times as the War went on. At the beginning, doctors from all sorts of disciplines were recruited, and only a few had adequate surgical experience. They all had a baptism of fire and those that had little experience soon gained it. Amputations increased. The further the War progressed, the attitude changed again, with many surgeons adopting the conservative approach, to try to save the limb.

During the Civil War over seventy per cent of wounds involved the upper or lower limbs.

Circular or Flap operation?

Another debate that ran throughout the War was which type of amputation operation to use. The older method was called the 'circular' operation. This involved using a tourniquet and making a circular incision around the limb, cutting through the skin and the fascia. An assistant then retracted the skin and the surgeon made a further circular cut close the skin incision and went through all of the muscles to the bone. The amputation was then done, involving ligature of vessels, retraction of tissues and sawing through bone. The muscles were then drawn over the end and the skin brought down and strapped with adhesive, rather than sutured.

The newer method was the 'flap' operation. This had been developed in the previous century by William Cheselden (1688-1752), an English surgeon. This was favoured by sixty per cent of surgeons. It involved sacrificing more bone, but it gave a better stump, albeit it needed a large wound. Essentially, an oblique incision was made, so that a skin flap could be created in order to give better closure and better stump protection. It was also a faster operation and seemed to produce less post-operative pain. The skin was closed with interrupted sutures about an inch apart. Sometimes wire was used and sometimes silk. There were also single flap and double flap operations.

Phantom limb pain

After the War many amputees complained of pain, often excruciating discomfort where their amputated limb should have been. For example, they might have severe pain where they could still feel the foot that was no longer there. The year after the War Dr Silas Mitchell of Philadelphia opened a stump clinic, where he made observations of these symptoms and he wrote a paper in Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, in which he described for the first time phantom limb pain. He speculated that it was the result of injury to the nerves during the operation.

He was quite correct, but there was little that could be done.

Although we have a better understanding of this phenomenon now and a greater range of therapeutic interventions, yet it is still a significant problem for many amputees.

Although we have a better understanding of this phenomenon now and a greater range of therapeutic interventions, yet it is still a significant problem for many amputees.

Doctor George Goodfellow

The Tombstone doctor was the right man to have operate on you in the wild days of Tombstone. He became the foremost authority on gunshot wounds and a surgeon who pushed back the frontiers in many areas. He did amputations, reconstructive facial surgery and he was the first surgeon to perform perineal prostatectomy. As I mentioned in my blog last month, his work on the impenetrability of silk to bullets led to the development of bulletproof vests.

The Tombstone doctor was the right man to have operate on you in the wild days of Tombstone. He became the foremost authority on gunshot wounds and a surgeon who pushed back the frontiers in many areas. He did amputations, reconstructive facial surgery and he was the first surgeon to perform perineal prostatectomy. As I mentioned in my blog last month, his work on the impenetrability of silk to bullets led to the development of bulletproof vests.

But he was a scientist and he kept up to date with the developments of surgery, anaesthetics and medicine. He used Lister's aseptic methods and had a carbolic acid spray for use during operation. He was absolutely the right surgeon for Virgil Earp.

***