THE DOCTOR'S BAGthe blog about the medicine and surgery of yesteryear

Keith Souter aka Clay More

I certainly would not have the temerity to comment on his qualities as a soldier or leader, other than to say that he undoubtedly had personal charisma. In this blog I am going to talk about three men who proudly served under Custer in different capacities. And since this is a blog about medicine and surgery of yesteryear I shall begin with a doctor.

The Brave Doctor - The only Doctor to survive Little Bighorn

Dr Henry Renaldo Porter was not soldier, but a contract surgeon. As such he had served under General Cook in his Apache Campaigns in Arizona in 1872 and 1873. Cook rated him highly and cited him for conspicuous gallantry in the closing campaign in March 1873.

In May 1876 at the age of twenty-eight he entered a three month contract for the Sioux campaign. He was about to step into history. After the battle of the Little Bighorn, he returned to civilian life and set up a practice in Bismarck. He wrote an account of the battle in the Bismark Tribune, which they published under the heading The Brave Doctor :

At six o'clock we started. It was Custer's purpose at this time to charge the Indians in a body, he supposing that our presence had not been discovered by them. In a short time the scouts reported that we had been seen by the Indians. Custer then decided to divide the command. He sent Colonel Benteen with three companies to the left; Major Reno with three companies in the center; and he took three companies and was to go to the right, his idea being to surround the Indian camp. Captain McDougal was left in charge of the pack train. It was about ten o'clock when the command was divided. Just as we were ready to start, Custer came to me and said: 'Doctor, I would like to have you go with me, as you are younger and more robust and Dr. Lord, the chief surgeon is not feeling very well.' I replied, 'All right. I would much prefer going with you.' Custer then said, 'I will see Dr. Lord and ask him to consent.' We rode over to where Dr. Lord was, and Custer spoke to him about the contemplated arrangement. The Doctor replied: 'Not much. I am going with you.' The poor fellow in those few words saved my life and sealed his own doom. I went with Reno. We had proceeded but a short distance when Captain Cook [Lt. W.W. Cooke], Custer's adjutant, came up and said: 'The Indians are right ahead of you, and you are ordered to charge them as fast as possible.

For two days Porter was the only doctor left alive and he cared for around thirty wounded men in an improvised field hospital in the Reno-Benteen defence. All this time he was under continuous fire from Sioux and Cheyenne rifles.

With limited medical supplies, he used laudanum, operated to remove projectiles and performed two amputations.

He was considered one of the heroes of the campaign. He was called to testify at the Reno Court of Inquiry in 1879. He died on a world tour in Agra, India at the age of 54 in 1903.

Old Neutriment

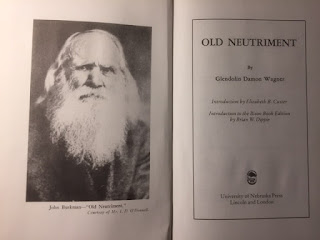

The second man to have served under Custer was John Burkman, his orderly for nine years up to the Battle of the Little Bighorn. His nickname was because of his raids on the kitchen at Fort Lincoln in his younger days.He was devoted to both George Armstrong Custer and to his wife Libby Custer. In his own words some years after the battle, " Seems like they want no use me goin' on."

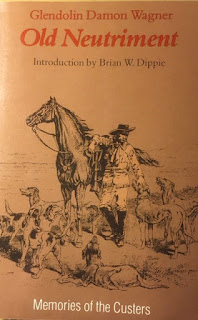

John Burkman was illiterate, but he shared his memories of living and working with the Custer's with his friend I.D. 'Bud' O'Donnell and all of this, complete with photographs, Gwendolyn Damon Wagner wrote in her book, suitably titled Old Neutriment in 1934. It gives some wonderful insight into his relationship with Custer and his personal views on the battle and the actions of the other major participants.

Buckman looked after Custer's two horses and his string of hunting dogs. He did so with love and meticulous care.

Like Dr Porter he had a fortunate escape from fate, albeit he bitterly regretted that he could not be at the end with Custer. This is a letter he dictated to an amanuensis to Mrs Custer in 1910:

"[Custer] turned to me with 'Burkman, saddle up my war horse, Vic: and you will have to remain with the pack train as I issued orders that there were to be no led horses in the front."

The men were all in good spirits when they passed me. Then was the time I begged his nephew, Arthur Reed, to remain back with me for i would rather have taken my chances in the front, but you know, I had to over orders. I could tell you word for word, Mrs Custer, if I were beside you. That was the last I saw of the General as they left the pack train."

Of Dr Henry Porter, John Buckman had only good things to say.

"Don't git me wrong, Bud. We want all cowards. A lot o' gallantry was showed that day. Some men volunteered to go down right in the face o' Indian fire, to rescue the wounded that was strung here and thar 'long the side o' the cliff. We was all cravin' water. The wounded suffered most.Doctor Porter - he was a good one and a brave fellow -- he worked like a beaver, easin' the sufferin' best he could. What with the heat, blood pizen set in quick. I seen him, one time in partic'lar, amputize a fellow's leg. I seen the man lay thar, his face white's a sheet, his lips set tight, not a moan out o' him, nothin' but his eyes tellin' how it hurt. Doctor Porter says, `My wounded has got to have water! Who'll volunteer to go arter it?'

"Bud, thar was the river jist below us, millions o' gallons of water a-ripplin' and a-sparklin' along, but betwixt us and it was the Indians, shootin' any one that made toward it. A deep ravine led from our hill and men could crawl down through it almost to the river but then there was a short stretch of open space and to dash across it to the water meant death, sure's sartain. Our hankerin' fur a drink got terrible. We sucked raw potatoes. We held pebbles in our mouths. Nothin' helped much. We'd all of us, horses and men, 've sold our souls fur a drink o' that water we could see flowin' along; but the wounded, o' course, was in the worst fix. When Doctor Porter spoke up some men volunteered and crept down the ravine carryin' buckets and kettles and canteens. I started with them. My horse got hit in the flank and I come back, figgerin' I'd jist as soon die of thirst as an Indian bullet. Some of 'em made it. One fellow was hit jist as he stooped over to fill his bucket and the pail was shot away and his leg was shattered. He hung on to another fellow's stirrup and was dragged back up the hill. Arterwards that leg had to be amputized. Most o' them that went down brung back a leetle water, jist enough so' the doctor could trickle it into the mouths of the wounded. Arter that from time to time men kept slippin' down through the ravine to the river, but I didn't try it agin.

Sadly, in 1925, having lived long after the battle he was found dead on the porch of his boarding house in Bilings, Montana, a gun in one hand and a bag of candy in the other.

James Kelly was born in Manchester, England in 1834. He was Custer's orderly and served under him until they came to Fort Dodge in 1872. Like Custer he loved horses, hunting and racing dogs, especially greyhounds. He was honourably discharged in 1872. As a parting gift Custer gave him a dozen greyhounds, hence the name 'Dog Kelley.'

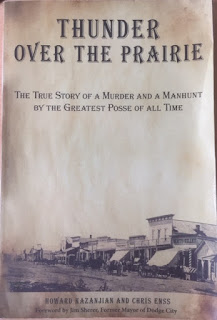

The story of this whole tragic episode is told in Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss's excellent book Thunder Over the Prairie.

Dora Hand was interred in Boot Hill.

As for Dog Kelley, his fortune came and went. He ran the Kelley Opera House in Dodge for several years, but lost his property in the Panic of 1884. He saw his last years in Fort Dodge, and himself died from consumption in 1912. He was buried in Fort Dodge cemetery.

Ned Buntline

The famous King of the Dime Novelists, Edward Zane Carroll Judson (1821-1886) was a fascinating character. He was a prodigious writer of popular literature who had clearly led an adventurous and very full life, and who saw no problem in aggrandizing himself and his achievements. He has been described by as The Great Rascal, which is not far off the mark, in my opinion. Yet that is not to denigrate him, for he produced a body of work that influenced and entertained millions of people. He introduced Buffalo Bill and Wild Bill Hickok to the wider world.

One of the fascinating things about him was the fact that not only did he create his own history (for example, he bestowed the rank of Colonel upon himself, although he had never been more than sergeant), but myths followed him.

He wrote hundreds of dime novels and is credited with having more or less created the mythic Wild West. Most western enthusiasts know about the Buntline Special, the extra long Colt revolvers that he allegedly had made for Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson and a few other famous lawmen who were involved in the posse that tracked down Spike Kenedy. Yet the historical records of the Colt Manufacturing Company fail to record their order, let alone their manufacture. It seems that this myth may have been created by Stuart N Lake, in his novel Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, published in USA by Houghton Mifflin in 1931 (and published as He Carried A Six-Shooter in the UK in 1952). William Shillingberg wrote a detailed, scholarly paper debunking this in 1976.

My own short biographical novel The Dime Novelist about Ned Buntline, published in the West of the Big River series by Western Fictioneers includes, with some poetic licence, the episode about Dora Hand and the fabled Buntline Specials.