|

| Cicero Rufus Perry |

Whenever someone comes up to me and says something like, “Your relatives were horse thieves,” I grin and give my shoulders a little shrug. My reply is: “Maybe some of them were, but I love my family anyway,” and that usually shuts them up.

The Texas Rangers have been taking

quite a hit lately from qualified historians, the armchair variety, and the

sensation seekers, mostly the latter. Whenever I read about their supposed

brutality, racism, etc., my response is the same. I love them anyway.

In Texas during the 1800s, there

was a group of Indians who loved to steal horses and a group of white men who

loved to chase them. Let them hear of a neighbor being scalped, horses stolen,

or women and children kidnapped, and they would drop the plow handles so fast

the dust didn’t even have time to settle before they would be gone—riding as

good and as fast a horse as they could saddle in the race to catch the

perpetrators. Most entered into the

service of the Texas Rangers at one time or another.

Certainly, the Indians, the women,

the slaves, the children, and the old people who were forced to stay behind and

do the everyday work deserve to have their stories told—but this blog is about

Texas lawmen. And Cicero Rufus Perry was one of those men.

“Old Rufe” as he came to be called, left Alabama and arrived

at Bastrop, Texas, in 1833 when

|

| Gen. Edward Burleson |

he was 11 years old. Bastrop, situated on the

banks of the Colorado River along the Old San Antonio Road, had Indian raids

every “light moon.” Indians stole all the Perry horses as soon as they arrived.

Consequently, young Rufe developed a case

of hero worship for one of the best Indian fighters of the time, Edward

Burleson. Burleson later led the Bastrop men in the charge at the Battle of San

Jacinto and became vice president of the new Republic of Texas. At one time, he

was just about the most popular man in Texas.

|

| Gen. Sam Houston |

But whereas Sam Houston was an

attention grabber who jumped in front of the camera in showy clothes at every

opportunity, Burleson only had his picture taken once, and that was at the

insistence of his daughter. He was a down-to-earth man who accepted

responsibility but never trampled anybody to get it. Much to the disgust of his

longsuffering wife, however, he was always willing to drop everything to pursue

Indians.

If Rufus Perry wanted to be an Indian fighter, soldier, and Ranger,

he learned from the best. At age 13, he and

his father were with the other Texican soldiers as they retreated toward San

Jacinto after the fall of the Alamo. Maj. Alexander Somervell approached the

boy—they needed someone to go to Capt. Mosely Baker’s camp at San Felipe some 30

miles away and give him a dispatch from Gen. Houston. He was to burn the town

so the advancing Mexican army couldn’t profit from it. No one else wanted to go.

Would Rufe be afraid to take it?

|

| San Felipe was second only to San Antonio as a commercial center - its destruction upset many Texans. Houston would later claim he never gave the order to burn it, infuriating Capt. Mosely Baker. |

“I toald I woold take it whitch I did” the semi-illiterate Perry

wrote later.

Perry continued to run dispatches for Houston, and after the

Battle of San Jacinto, he joined the Texas Rangers, continuing in that capacity

as a regular and volunteer for the next 40 years, chasing marauding Indians,

Mexican bandits, and thieving outlaws. He first volunteered for duty under Capt.

William W. Hill whose company was attached to Gen. Edward Burleson’s Rangers.

They were all that stood between the settlers returning home and rampaging

Indians emboldened by their evacuation.

While Perry honed his Ranger skills under the tutelage of

Burleson, he was receiving an education about life on the raw frontier. He

watched in disgust as one “desperado” they had riding with them jumped on the

first dead Indian he came to and began stabbing him. Perry remarked wryly, “I

think if hee had of bin a live hee woold have went the other way.” Another

shock came when an old backwoodsman cut the thigh off a dead Indian and tied it

to his saddle, saying he was going to eat it if they did not get anything in

the next few days. Fortunately, they made it to someone’s house, and “got beeaf

and raostinears then wee dun fine.”

It is important to note, according to historian Donaly E. Brice,

that up until the Battle of Plum

Creek in 1840, the fight against Indians in

Texas was a defensive one. Horses would be stolen, people killed or kidnapped,

and then the Rangers would go after them. In 1839, 16-year-old Rufe joined Col.

John Moore’s company of men that included 42 Lipans for an expedition against

the Comanche. At San Saba, they were able to surprise the enemy, and a battle

ensued. Comanche women and children fled wildly into thickets. Andrew Lockhart,

whose daughter had been kidnapped, ran ahead, screaming her name. Although the

men were brave and experienced, the expedition had been poorly planned and

executed. Under a white flag, a parley

was held between the whites and Comanche, with the Lipans translating.

The

Comanche tried to bluff the whites with a threat of nearby Shawnee, while the

Lipan translator convinced them the whites had no wounded. Badly outnumbered by

the Comanche, they agreed to a truce. When they returned to where their horses

had been, it was to find that every horse, blanket, and saddle had been stolen.

Rufe joined the others in walking the 150 miles home.

This humiliating episode did nothing to dampen Perry’s

fighting spirit, and he continued to serve and scout for the Rangers. In his

memoirs, he talks openly about taking a scalp because a young lady in Bastrop

asked him to bring her back one. “hee fell as tho hee was dead and wee thaught

hee was but when I went to raze his top not hee razed with me I tell was had a

liveley time for a while until oald butch got the best of him.”

|

| Punch Nash is about to drive his stagecoach across the Colorado River in Bastrop, TX |

Perry relates an incident that happened the next day just as

frankly. The Rangers, along with some Lipan Indians, were on the trail of

Comanche, killing two. The Lipans took a woman prisoner. “the way the friendly

Indions did to ceap hur was to Sleap with hur each one evry night as their time

come young Flaceo toald mee to tell Coln Lewis hee and mee could sleap with hur

when thay all went around as he was commander and I interpretor but wee did not

but let them have hur to them selves.”

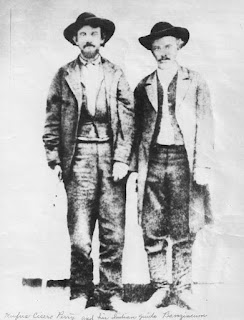

|

| Rufus Perry and his Indian guide Banzincum |

In the meantime, an obsessed Santa Anna was unwilling to let

Texas go and would continue to send soldiers in attempt after attempt to conquer

the Texans, and Perry participated in stopping them. Although the Mexican

American War is now deemed unconscionable by some historians, it was the only

thing that finally put a halt to Mexico’s invasions into Texas.

After three predatory raids by Mexican soldiers into Texas,

in a political move intended to stop the outcry of settlers, Gen. Houston

allowed Alexander Somervell to lead a raid into Mexico. Perry again joined up,

and as Houston expected, with little equipment and supplies, it showed how

futile a raid into Mexico could be, and it had to be aborted. Perry was one of

the 189 men who obeyed Somervell’s order to return home—308 men disobeyed and

continued on in what became known as the Meir Expedition, leading to

imprisonment and the infamous black bean episode.

|

| Capt. Jack Coffee Hays, a great nephew of Andrew Jackson's wife, was the first to use the Navy Colt Paterson five-shot. He later helped Samuel Walker get to New York so he could meet with Samuel Colt and redesign it into the legendary Colt Walker six-shoot revolver. |

In 1844, Perry joined the legendary John Coffee Hays’s Ranger

company and participated in many more Indian battles. On the Nueces River, an

incident happened with three other Rangers that was to add Perry’s name to the

legend.

The Rangers were on

the trail of horse thieves, and Perry told the other men to camp on a bluff

while he continued a short distance ahead. When he returned, he saw they had

not camped on the bluff, but closer to the river. He told them Indians would

not have camped in such a spot, and he felt they weren’t far off. He rode up a

hill to have a look, but couldn’t see signs of any Indians nearby. He went back

to camp to eat, all the while having a premonition that things were about to go

wrong.

Two of the men went to the river to bathe, but Perry and the

other ranger, Kit Acklin, refused to join them. The men had just shucked off

their clothes when Perry and Acklin were attacked by about 25 Comanche. Perry

received one shot through his left shoulder, all the while firing his five-shooter

at the enemy. He received another shot through his belly, and the third on his

temple, cutting an artery so that he temporarily fainted from loss of blood.

|

| Although the Colt Paterson gave the Rangers an advantage in the field, it had to be disassembled into three pieces before it could be reloaded. |

|

John Holland Jenkins,

Perry's boyhood friend. |

Perry later told his friend and fellow Bastropian John

Holland Jenkins that when he came to, he put the gun to his head, considering

suicide with the last bullet rather than be taken by the Indians and tortured. But Perry realized he could move, and he was able to join Acklin at the river, and

he pulled the arrow out of his shoulder, leaving the spike. Perry caught hold

to the tail of one of the horses and got across the river to where the other Rangers

were, but he fainted once more. One of the Rangers had taken Perry’s gun to

reload it when they were attacked again. Panicking and thinking Perry wouldn’t

live anyway, they took his gun and ran off, leaving him and Acklin to the

Indians. Perry was able to crawl to a nearby thicket and hide while Acklin made

his escape. (Another account has Acklin being much more proactive in helping

Perry—only leaving after both agreed that splitting up and going for help

separately would be better.)

Perry could hear the Indians talking and walking around the

thicket, but perhaps thinking he was armed, decided to leave him alone, and

they soon left. He stuffed his wounds with dirt and little sticks to staunch

the bleeding, and once it was dark, he crawled on his hands and knees down to

the river for water. It was only about 200 yards, but it took him from dark to

daylight to get there. After getting his fill of water, and filling up his boot

with more, he crawled to a hole left by a fallen tree and stayed there all day.

At nightfall, Perry started for San Antonio on his own. On

the seventh day he reached San Antonio after walking 120 miles with nothing but

three prickly pear apples and a few mesquite beans to sustain him. People

stared at him as if seeing a grisly ghost, for the two Rangers who had taken

the horses and run away had arrived before him, naked and horribly burned from

the sun, telling everyone he and Acklin were dead. Acklin, who wasn’t in nearly

as bad a shape as Perry, made it into San Antonio the next day.

|

| San Antonio as it was a few years after Rufus Perry walked into town, a bloody, swollen mess. |

The women of San Antonio took such good care of Perry, to his

dying day he praised them, two in particular, a Mexican woman he called Madam

Androon, and a German woman named Mrs. Jakes. It took him two years to recover

from his wounds. They counted twenty holes in his clothes where arrows had

pierced them. The optic nerve in his right eye was severed, disfiguring it, and

for the rest of his life, it twitched. He was 22.

While recuperating at home in Bastrop, Perry married a beautiful

young woman described in later years as being somewhat haughty. But Perry must

have been perceived as something of a hero. As soon as he recovered enough to

ride, the people of Bastrop County presented him with a fine horse. He later served

two years in the Mexican War with the Texas Volunteers and afterward served again

with the Rangers, being stationed in the Texas Hill Country. In 1851, he left

Bastrop and began moving ever westward, finally settling in Blanco County.

Although the owner of four slaves, he sidestepped the Civil War, joining the

Confederacy but leading forces in frontier protection, preferring to fight

Indians, not Yankees.

|

The first time Samuel Walker

went out as a Ranger, he

accompanied Rufus Perry.

|

|

Half of the Perry cabin was restored

and brought to Johnson City, but

it has since fallen into disrepair. |

|

The Perry cabin would have originally

resembled this other Pedernales River cabin. |

|

Rufus Perry's daughter said

when she was a little girl, they were

attacked by Indians on their way

home from Fredericksburg. Everyone

was handed a rifle, including her

and her two brothers. When the smoke

cleared, three Indians lay dead and

another wounded. |

|

| Pedernales River - rugged and beautiful. |

The end of the Civil War brought about a social collapse in Texas

and a period of unprecedented lawlessness. Not only were there bandits

harassing ranchers on the border, Indians harassing citizens on the western and

northern frontier, there were former soldiers wandering around, suffering from

disillusionment and extreme trauma, falling into outlawry. Other ruffians used

the defeat of the South as an excuse to go on crime sprees. When it became

clear the U.S. government was only too happy for Texas to suffer for her

misdeeds, Governor Richard Coke recommended Texas form her own forces to

protect the frontier. When the citizens of Blanco County found out, they

requested “Old Rufe” Perry be made captain of Company D, and his approval was

soon forthcoming. In 1874, at age 53, he was back in the saddle again, wasting

no time in raising a company of 75 men. He

immediately put his men out in the field, arming them with shotguns for guard

duty, 61 Sharps Carbines, 57 Colt revolvers, and 900 Winchester cartridges for

those who carried their own 1873 Winchesters. Capt. Perry organized the

fledgling company, getting it off the ground and leading it through skirmishes

and battles, but when budget cuts came down from the legislature, he resigned

in 1875. By 1881, life as a Ranger as he

knew it had changed and passed him by.

|

| Company D men on the Leona River |

|

| A Ranger camp in the 1870s. |

Cicero Rufus Perry began life as a young man full of vigor

with a head full of gorgeous dark hair and a dancing gleam in his eyes. Before

he died, his face was scarred, with one eye distorted and twitching, and he had

to walk with a cane. But he never lost his love of the chase or his sense of

humor.

As an old man, he wrote: “when I first wint thair (to Blanco

County), there was Indions nearly evry light moon I was oute verry often but never caught up

with them but once thair was but 2 of us

and 40 of them So wee dun the runing.”

Old Rufe had the courage and the grit, packing as much dangerous

and exciting service into his lifetime as any other Texas Ranger. People who

knew him well liked and respected him. So why isn’t he more famous?

Like his hero Gen. Edward Burleson, Rufus Perry didn’t chase

fame. His near illiteracy also held him back. In an era when men refused to say

the word “bull” around ladies, his frank earthiness didn’t always fit into

polite society. He hadn’t gone off to fight the Yankees with the rest of them,

but stayed to do battle on the frontier.

In addition to those drawbacks, Perry had become involved in

a relationship with a widow who had eight children. How a man, honorable enough

not to participate in the gang rape of an Indian captive on the frontier when very

few people would have ever known about it, managed to get himself entangled in

a public web of having offspring with a widow while still having children with

his wife, is a head-scratching mystery.

But Cicero Rufus Perry never let the opinions of others get

him down. What went on between him, his wife, and his lover, we’ll never know.

When he died, old and feeble, he was not at home in Hye with his wife or in Austin

with the mother of his other children. He was at a neighbor’s ranch, and they

buried him all alone in the Masonic Cemetery in nearby Johnson City, while his

wife, who outlived him by several years, chose to be buried in Hye.

At the time of his death, Rufe Perry’s body showed twenty

scars made from bullets, arrows, and lances in his quest to retrieve stolen

horses, to keep women from being kidnapped and raped, children from being

snatched from homes, and to rescue them when they were. If he stumbled

sometimes in life, it didn’t matter to his friends and neighbors. They

continued to hold him in high esteem.

Perhaps somewhere in another dimension, there are Indians

stealing horses with glee from Anglo settlers, and Old Rufe Perry and his fellow

Rangers are excitedly saddling up to chase them once again—and neither party

gives an owl’s hoot about what we think.

And that’s just as it should be.

Sources:

“Memoir

of Capt'n C.R. Perry of Johnson City, Texas: A Texas Veteran” by Cicero Rufus

Perry, edited by Kenneth Kesselus. “Recollections of Early Texas—The Memoirs of

John Holland Jenkins,” edited by John Holmes Jenkins III. “Edward

Burleson—Texas Frontier Leader” by John H. Jenkins and Kenneth Kesselus.

“Moore’s Defeat on the San Saba” Frontier Times Magazine Vol 3 No. 5 February

1926. “One Of Our Texas Queens” Frontier Times Magazine Vol 21 No. 04 - January

1944. “Thrilling Escape of Two of Hays’ Texas Rangers” Frontier Times Magazine

Vol 06 No. 11 - August 1929. “Perry, Cicero Rufus (1822–1898)” Handbook of

Texas Online. “Savage Frontier: 1838-1839” by Stephen L. Moore. “Winchester

Warriors—Texas Rangers of Company D. 1874-1901” by Bob Alexander. “Texas

Rangers—Lives, Legend, and Legacy” by Bob Alexander and Donaly E. Brice. Donaly

E. Brice Speech, November 8, 2019, Bastrop, Texas. Email Exchanges, Lisa D.

Bass, Rufus Perry Cousin, February, 2022.

www.vickyjrose.com

www.easyjackson.com

BOOKS

As V.J. Rose

TREASURE HUNT IN TIE TOWN—Reader’s Favorite Five Star

Award

A rancher takes his nephews on an adventurous hunt for

buried treasure that lands them in all sorts of trouble. https://www.amazon.com/Treasure-Hunt-Town-V-J-Rose-ebook/dp/B07GL2T2L6/ref=sr_1_1?crid=SFQM7U0AN3FF&keywords=treasure+hunt+in+tie+town&qid=1569773588&s=books&sprefix=treasure+hunt+in%2Cstripbooks%2C201&sr=1-1

TESTIMONY

Two lonely people hide secrets from one another in a May-December

romance set in the modern-day West. https://www.amazon.com/Testimony-V-J-Rose-ebook/dp/B07FBC971J/ref=sr_1_2?crid=SFQM7U0AN3FF&keywords=treasure+hunt+in+tie+town&qid=1569773615&s=books&sprefix=treasure+hunt+in%2Cstripbooks%2C201&sr=1-2

As Easy

Jackson

A BAD PLACE TO DIE—Will Rogers Medallion Award and

A SEASON IN HELL

Tennessee Smith becomes the reluctant stepmother of three

rowdy stepsons and the town marshal of Ring Bit, the hell-raisingest town in

Texas. https://www.amazon.com/Bad-Place-Tennessee-Smith-Western/dp/0786042540/ref=tmm_mmp_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1569773439&sr=1-1

https://www.amazon.com/Season-Hell-Tennessee-Smith-Western/dp/0786042567/ref=pd_sbs_14_1/132-7644810-2844345?_encoding=UTF8&pd_rd_i=0786042567&pd_rd_r=f5f73ea9-df93-46e7-b002-87cd61097ca1&pd_rd_w=xTzD8&pd_rd_wg=OsUzo&pf_rd_p=d66372fe-68a6-48a3-90ec-41d7f64212be&pf_rd_r=FDF2CTCM49RMWFJ0WXXC&psc=1&refRID=FDF2CTCM49RMWFJ0WXXC

MUSKRAT HILL—Peacemaker Finalist

A little boy finds a new respect for his father when he

helps him solve a series of brutal murders in a small Texas town. https://www.amazon.com/Muskrat-Hill-Easy-Jackson/dp/1432866044/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=muskrat+hill+by+easy+jackson&qid=1581181324&s=books&sr=1-1

Short Stories:

WOLFPACK PUBLISHING - "A Promise Broken - A Promise

Kept"—Spur Award Finalist

A woman accused of murder in the Old West is defended by

a mysterious stranger.

https://www.amazon.com/Promise-Broken-Kept-Western-Short-ebook/dp/B07CYP3G3P/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=a+promise+broken+a+promise+kept+by+VJ+Rose&qid=1569773655&s=books&sr=1-1

THE UNTAMED WEST – “A Sweet-Talking Man” —Will Rogers

Medallion Award

A sassy stagecoach

station owner fights off outlaws with the help of a testy, grumpy stranger. A

Will Rogers Medallion Award Winner. https://www.amazon.com/Untamed-West-L-J-Washburn-ebook/dp/B07GH7WB58/ref=sr_1_3?keywords=the+untamed+west+anthology&qid=1569773750&s=books&sr=1-3

UNDER WESTERN STARS - "Blood Epiphany"—Will

Rogers Medallion Award

A broke Civil War veteran's wife has left him; his father

and brothers have died leaving him with a cantankerous old uncle, and he's

being beaten by resentful Union soldiers. At the lowest point in his life, he

discovers a way out, along with a new thankfulness. A Will Rogers Medallion

Award Winner.

https://www.amazon.com/Under-Western-Stars-Richard-Prosch/dp/B08KH3S2KR/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

SIX-GUN JUSTICE WESTERN STORIES – “Dulcie’s Reward”

Seventeen-year-old Dulcie is determined to find someone

to drive her cattle to the new market in Abilene. https://www.amazon.com/Six-Gun-Justice-Western-Stories/dp/B09FCCLTHQ/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

Reenactment Video on YouTube “Blood in the Streets” https://youtu.be/vrW_uFBGe8Q

Anthology:

WHY COWS NEED COWBOYS: AND OTHER SELDOM-TOLD TALES FROM

THE AMERICAN WEST

“Katie Jennings & John Holland Jenkins: Young Heroes

in the Fight for Texas Independence”

https://www.amazon.com/Why-Cows-Need-Cowboys-Seldom-Told-ebook/dp/B08YWJDGZ8/ref=sr_1_1?crid=2S1C6UIQO4IZ9&keywords=why+cows+need+cowboys&qid=1645144537&s=books&sprefix=why+cows+%2Cstripbooks%2C110&sr=1-1