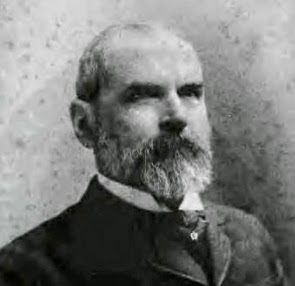

Julian John Chisolm, often referred to as john Julian Chisolm or as J.J. Chisolm was born in Charleston, South Carolina in 1830. He obtained his MD medical degree from the Medical College of South Carolina in 1850 then travelled to Europe to study medicine and surgery in Paris and London.

He returned to Charleston in 1860 and took up the post of Professor of Surgery at the Medical College. He kept the position throughout the War and in 1861 published the first edition of his textbook A Manual of Military Surgery for the Use of Surgeons in the Confederate States Army.

He was one of the few competent surgeons at the start of the War (it was the steepest of learning curves for surgeons on both sides), but his book gave detailed instructions. His experience was based on personal observations of many wounds treated in both civilian and military hospitals admitted form the battlefields of Europe. The book was updated twice during the War.

PUNCTURED WOUNDS, MADE BY THE BAYONET OR SABRE, require similar treatment to gunshot wounds. If the history and appearances clearly indicate the character of the wound, there will be no need of probing for imaginary foreign bodies. Such wounds usually bleed more freely than gunshot wounds, but the haemorrhage is susceptible of control by similar means - pressure being preferred to ligation of arteries. The treatment should be cold water dressings - irrigation preferred. Protect the wound from air, if possible, by covering it with adhesive plaster or collodion, and dress it a seldom as possible, compatible with cleanliness. Once, probing such a wound should satisfy the curiosity of any surgeon. A frequent repetition of this meddlesome surgery, besides the needless pain inflicted upon the wounded man, must end in mischief.Simple incised wounds, as sabre cuts, will be closed by adhesive plaster (or sutures, which are preferable, should there be any tendency to gaping), to be followed by the cold water dressing. Should the wound be not of a serious character, it may be left even without after-dressing - the little oozing from its edges, when drawn together by straps or sutures, dries into a scab along the line of the wound, and excludes air with its pernicious influences. This permits of the remodelling process and cicatrisation is effected without suppuration.Should a bayonet or sabre wound transfix one of the natural cavities, the internal injury may be rapidly fatal from hemorrhage , or the injury inflicted upon the contained organs may, sooner or later, lead to the destruction of the patient by visceral inflammation. Under ordinary conditions, when such wounds exist in the extremities, where no large vessels are implicated, they require no special treatment. It is a class of wounds not as frequently met with in military surgery as one would suppose. The sabre-bayonet, when plunged into the body among the viscera, leaves but little work for the surgeon. Such cases seldom leave the battlefield alive.When the ordinary bayonet has buried itself deeply in a limb, suppuration may appear in the course of the wound. Should pus b suspected, and fears exist that it may be pent up under a fascia, it would be necessary to dilate the wound t permit of its free escape. Under no other condition should a punctured wound , made by either a sword or bayonet, be dilated, except to remove foreign bodies or to control serious haemorrhage, where it is necessary to ligate the open mouths of the bleeding vessel.

.png)