The rental car agent was not talking me out of my six-dollar-a-day Tahoe.

“How

about upgrading to that Camaro out by the curb?” He chin-pointed to a spot

beyond the window. “Pretty day for a convertible.”

|

| I don't think so... |

I

glanced at the chrome yellow muscle car, complete with a Transformer Bumblebee

stripe on its rakish hood. “No, thanks.” I was smug in the knowledge that the

ridiculously low rate I’d scored on a discount travel site was actually for

real.

Focused

on the add-on sale, he threw out more bait. “You’ll need GPS, right? And the

insurance?”

I

felt a crack in my smugness. “Um, no insurance. But…how much is the GPS?”

“Fifteen

a day.”

“Nope.”

Whew. He almost had me. “I’ll just keep what I’ve got.” Meaning, my smart phone

and a file folder stuffed with maps and notes I’d printed at home. Grudgingly,

he slid the key across the counter.

“Gold

Tahoe. Space 441.”

No

“have a nice day, thanks for choosing us,” no “take a left outside the lot to

get to I-25,” no nothing.

Fifteen

minutes later, I was hopelessly lost in a shadowy Denver warehouse district,

looking for a place to turn a Tahoe around. By the time, I surfaced into

sunshine on an interstate ramp and shoehorned into the northbound stream of traffic,

I was running an hour behind my projected schedule. But what's a little lost time and traffic, when there's a meander along a two-lane, mountain highway on the agenda?

I

planned to drive the 101-mile Cache la Poudre Scenic Byway from east to west

via Highway 14, which hugs the river from the foothills near Ft. Collins to the

North Park region of Colorado. The Cache la Poudre has been designated as

Colorado’s only National Wild and Scenic River and its name translates roughly

to “hide the powder,” possibly in reference to early fur traders who stashed their

gunpowder along its banks. Brown and rainbow trout are plentiful, making it a

popular spot for anglers. Rafting enthusiasts enjoy the Poudre’s thrilling

rapids and there are outfitters located along the route.

|

| That's why we call them the Rockies. Highway 14, west of Ft. Collins |

For

the first several miles, the river burbled amiably to my left – then the gentle

shale outcroppings along the highway merged into sheer granite walls as the

road began to climb toward the river’s headwaters in the Rockies. The vertical

slabs were only a few feet from the road’s edge. This was where the Cache la Poudre

began to tout its “wild and scenic” status. High and fast with June snowmelt,

the river roiled and tumbled over boulders. I lowered my windows to better hear

the roar of the rapids.

|

| Peaceful Poudre |

|

| Picking up the pace |

The

striking thing about this byway is the way the terrain changes every few miles.

I drove out of the rocky pass into a wide valley, rimmed by peaks still

glistening with snow. The river ran flat and broad. Brown-vested fishermen

stood knee-deep, casting fly lines into long, high spirals. I passed numerous

cottonwood-shaded campgrounds, scattered with tents and travel trailers.

|

| Fly fishing heaven |

Beyond

the valley, the highway snaked up into the peaks of the beautifully named Never

Summer Mountains. Patches of snow lay in the shadows of evergreens. The Poudre

was back to whitewater, pounding against the sides of the canyon and constantly

switching from one side of the highway to the other. I stopped on one of the

bridges to take photos, aware of the incredible force of the rapids below me.

|

Eventually,

the highway straightened onto a high basin 8,800 feet above sea

level. Just before I reached Chambers Lake, the Poudre veered off to the south and the road curved into the billowing North

Park grasslands. I spotted herds of antelope grazing alongside cattle. The

plains encompass over 1,600 square miles and are rimmed by the Rabbit Ears and

Medicine Bow mountain ranges. From those distant peaks flow the headwaters of

several rivers of Western lore: the North Platte, the Michigan, the Illinois,

the Canadian.

| |||||

| North Park plains |

I

ended my Cache la Poudre adventure with an Angus burger at River Rock Café in

Walden, the “Moose Viewing Capital of Colorado.” I took a stroll through the

delightful North Park Pioneer Museum – three floors and twenty-seven rooms

packed with incredible artifacts and memorabilia donated by the area’s first

settlers. The curator was a native son and seemed glad to field my many

questions. (I sheepishly revealed that my curiosity was part and parcel of

being a writer.)

After

my tour, he followed me outside to point me toward my next stop, Wyoming. I

waved farewell and started the engine. The Tahoe picked a sure footing through the potholes and sharp rocks of

the parking lot, and nosed onto the road to Cheyenne.

Nope. We wild-hearted mountain explorers don’t

drive no stinking yellow Camaros.

Click here for more information on the Cache

la Poudre Scenic Byway.

All the best,

Vonn McKee

“Writing the Range”

2015 WWA Spur Finalist (Short Fiction)

2015 Western Fictioneers Peacemaker Finalist (Short Fiction)

Follow me on Facebook!

|

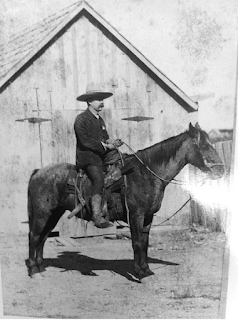

| My trusty Tahoe... The best six dollars a day I ever spent. |