THE DOCTOR'S BAG

The blog about 19th Century Medicine and Surgery

By Keith Souter aka Clay More

TREPHINATION AND HEAD INJURIES

Head injuries are common in tales about the Old West. That is not surprising, considering all those gunfights, fist-fights and falls from horses. The town doctor on the frontier would probably have to be adept at treating them. That could include trephining the skull - effectively, opening the head.

Treatment of a skull injury from Fieldbook of Medicine 1517

Nowadays we have CT and MRI scans which can give us sophisticated images of the body. A CT scan stands for Computerised Tomography, which involves taking x-rays of the brain from various angles, which are analysed by a computer to build a 3-d image of the brain. This will show any fracture or haemorrhage. A MRI scan stands for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. It uses magnetism, ultrasound and computerised technology to build up images of the inside of the body. These can show the tissues and any abnormalities in surprising detail.

Back in the Old West there were no such luxuries. X-rays were only discovered by William Roentgen in 1895. The first use of them diagnostically only started the year after when Dr John Hall-Edwards in Birmingham, England started to use the technique. The town doctor had to use his clinical skills.

The unconscious patient

The doctor would assess the patient, by examining the scalp for a wound or local bruising. He would examine the ears and nostrils for bleeding, both of which could indicate a significant head injury, with fracture of skull bones.

Coma is the state of absolute unconsciousness when the patient does not respond to any stimulus. Squeezing the ear lobe or using the knuckles of the hand to rub over the sternum (breast bone) are extremely painful and usually will evoke a response in someone who is in a semi-coma. This means that they only respond to painful stimuli. A full coma patient will not even respond to pain.

The pulse would be taken frequently, say every 15 minutes in an unconscious patient. A slowing of the pulse is called bradycardia and may indicate internal hemorrhage somewhere, possibly inside the skull.

The semi-conscious patient

The patient may well be confused, so the level of confuse would be assessed. A rule of thumb gives mild, moderate or severe states of confusion.

Mild - some coherent conversation is possible

Moderate - out of touch generally, but will answer with name or occupation

Severe - no sensible answers given, but will respond to simple commands such as hold my hand.

Deepening confusion may indicate hemorrhage. Sudden vomiting may also be highly significant.

Examination of the cranial nerves

There are twelve paired nerves which come directly out of the brain to supply the head and neck and some of the internal organs. These are separate from most other nerves, which come out from the spinal cord.

1st nerve -

olfactory nerve - sense of smell

2nd nerve -

optic nerve - vision

3rd, fourth and sixth nerves -

occuolomotor, trochlear and abducent nerves move the eye and operate the pupils - get the patient to follow the finger and also shine a light in the eyes - the pupils should constrict

5th nerve -

trigeminal nerve - sensory to the face and operates the masseter muscles, the large muscle that moves the jaw - tested by asking to clench the jaw

7th,

facial nerve - movements of the face - ester by asking to see the teeth

8th,

acoustic nerve - for hearing. Can he hear?

9th

glossopharyngeal nerve - to the pharynx - cannot be tested

10th

vagus nerve - multiple internal functions, but also moves the palate - tested by asking the patient to say 'Ah.' The palate should move when he does

11th nerve -

accessory nerve - tested by asking to shrug the shoulders

12th nerve -

hypoglossal nerve - moves the tongue.

Significantly the movements should be equal on both sides. One sided results could indicate a problem with one side of the brain.

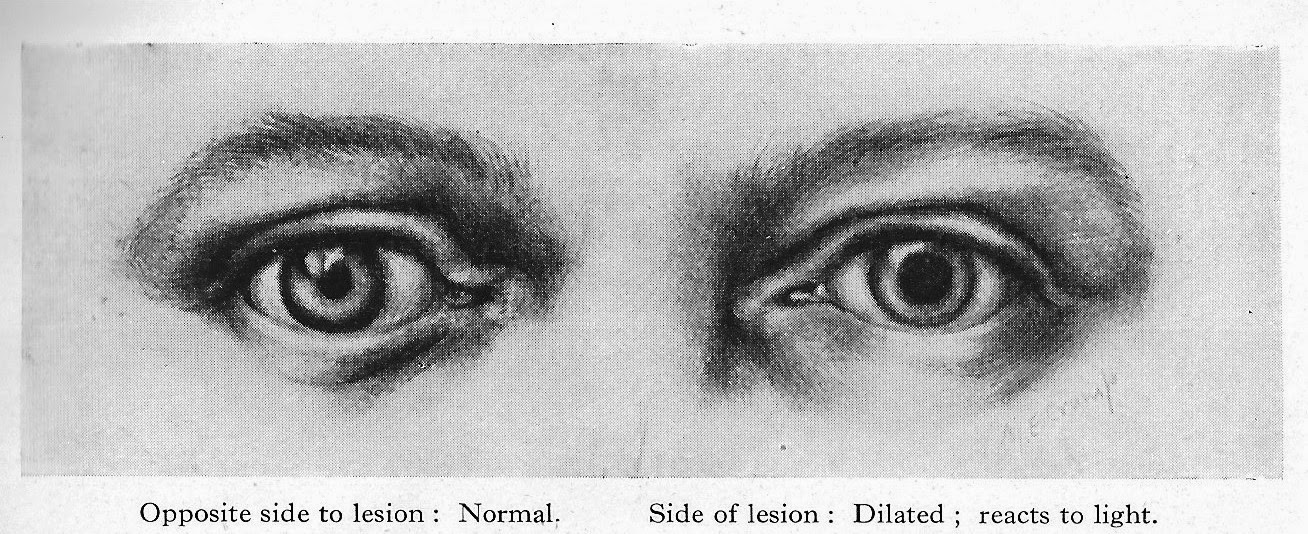

Hutchinson's pupils

These are a set of guidelines devised by Sir Jonathan Hutchinson (1823-1913), a professor of Surgery at the Royal College of Surgeons of London. He wrote a ten volume Archives of Surgery between 1885 and 1899.

Hutchinson's pupil, described by him indicates that an intracranial mass (a tumour or blood clot) will result in a fixed (meaning it will not change size even when light is shone on the eye) and dilated pupil on the same side. This is very significant, since it would indicate where to make the trephination.

General physical examination

Here the focus is on assessing the power of each limb and comparing one see of the body with the other. Disparity between the sides could indicate developing or developed paralysis.

Also testing the reflexes with a 'patella or tendon hammer.' The following reflexes are tested:

Biceps tendon by tapping the tendon in the hollow of the elbow.

Triceps tendon by tapping the tendon on the back of the elbow when the elbow is flexed.

Patella tendon by tapping underneath the stella (kneecap) with the leg flexed.

Achilles tendon by tapping the tendon at the back of the ankle.

Lack of reflexes on one side would be significant.

Trephination

The words trephination and trepanation are used interchangeably, since both come from the Greek trypanon, meaning 'to bore.' Archaeological evidence shows that trephination, the boring of a hole in the skull was used in early tribal societies. It was presumably thought that this would let out evil spirits. Examination of many skulls which have been trepanned in this way shows that healing of bone around the site of the boring took place, indicating that in many cases the operation was a success. Incredibly, they used three methods - cutting, scraping and drilling.

The oldest trepanned skull was found at a neolithic burial site at Ensisheim in France. It has been dated to 7,000 years ago.

The reason that it could have helped is by releasing the pressure upon the brain, which would follow a hemorrhage. Unfortunately, in those people who were not suffering from a rise in pressure it may have done actual harm.

The ancient Egyptians had actually developed a quite sophisticated system of medicine and surgery with doctors who specialised in one area of the body. thus they had eye doctors, stomach doctors and head surgeons.

The Edwin Smith papyrus, written in about 1500 BC, is essentially an ancient Egyptian textbook of surgery. It describes surgical instruments and techniques and discusses 48 cases of injuries, including head injuries.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus c 1500 BC - an ancient Egyptian textbook of surgery

A beautiful description of ancient Egyptian surgery is given in the 1945 historical novel The Egyptian by the Finnish writer Mika Waltari, which became an international bestseller and later a Hollywood blockbuster in 1954. In the novel the main character Sinuhe, who became royal physician to Pharaoh Akhenaten (father of Tutankhamen), is apprenticed to Ptahor, the 'opener of head.' He shows him how to examine a patient and diagnose where there may have been a problem in the head from an assessment of the state of consciousness and the use of the limbs. He then shows him how to remove a piece of skull and replace it with a silver plate which is bound with bandages while they await recovery.

Ancient Greek surgical instruments. Note the trephine in diagram 'a' with a central pin

The technique of trephination was also used by the Greeks and the Romans. The instruments required became increasingly sophisticated.

We're going to have to open his head

The experience of British surgeons with gunshot winds to the head during the the Crimean War (1853-1856) was not promising. Trephination was associated with an extremely high mortality of over 95 per cent. George H B Macleod, the chief surgeon of the British Expeditionary Force advise against the operation.

During the American Civil War the operation was performed with better results. The survival rate improved to more than 20 per cent. Then after Lister's aseptic techniques were accepted, recovery rates continued to improve.

In 1882 Samuel W Gross wrote a textbook A System of Surgery, in which he quoted a 41 per cent recovery rate after gunshot trephination.

The trephination operation

The instruments needed:

Trephine - a cutting instrument with a cylindrical blade - usually with a cutting circle of one inch

An antique trephine with horn handle

Chisel and mallet

Rongeur - a strong forceps for grasping bone

Also needed would be a scalpel and various forceps for holding tissues, a gouge for smoothing roughed or fractured bone edges and an elevator to lift the bone disc that was cut.

The operation

The patient's head would be shaved and washed. After Lister this would have been with carbolic soap and then it would be scrubbed and washed with a 1 in 20 solution of carbolic acid in alcohol.

The head would be supported on a sandbag and sterilised towels applied around the site to open the skull. In the earlier frontier days, this would not have been thought necessary.

When a wound already exists and a fractured spicule was apparent, the cite would be exposed by enlarging the wound. When the scalp was not wounded, as in a clubbing head injury or from a fall, then a semilunar flap of skin would be cut and raised. It would be cut so that the free end would point downwards. It would be a shallow curve, carefully made to avoid the main scalp arteries.

Alternatively, a V-shaped incision could be made, again with the V pointing downwards. It should be so arranged as to allow free-draining of blood.

The incision should be carried down to the bone and the tissues helped with forceps. Then the flap would be turned upwards. A suture would be placed through it so that the flap could be held out of the operative territory.

Any bleeding vessels would be secured with pressure forceps to close the vessels off.

Any spicules of fractured bone could be chiseled off with the chisel and mallet.

If there is no fracture, then the circular trephine is applied. The central pin could be bored into the bone, then the trephine is made to cut into the skull by light, sharp movements from left to right and from right to left.

At first bone dust is dry, but it soon becomes soft and bloody. Once through the bone, the pressure changes dramatically.

The area must be kept free of bone dust by irrigation with saline.

The trephine is then gently rocked back and forth to allow it to move, then the elevator is inserted. The ronguer forceps can then be applied carefully to remove the disc.

The blood or the blood clot can then be removed. It may well express itself. The area needs to be irrigated and any bone spicules or bone dust removed.

The bone disc is placed in a china cup and soaked with warm (sterilised) water, ready to be replaced.

Once replaced the skin flap is brought back into place with silkworm-gut sutures.

In later years a spiral rubber tube could be used to drain between the sutures.

It wasn't always a head injury

Abscesses could also cause raised intracranial pressure and need trephination.

Choosing the site of trephination was important, since you need to avoid the middle meningeal artery. The diagram shows the areas that were commonly used. They would avoid the area between A and B, since the artery runs underneath the cranium. Points A and B would be used if a middle meningeal artery haemorrhage was suspected.

This sort of hemorrhage can cause an epidural haematoma. This is a blood clot forming between the dura mater (the thick outer layer of the meninges, the membranes that cover the brain) and the cranium. Rupture of the middle meningeal artery is often the cause. It comes on after a head injury when someone is knocked unconscious. They then recover, seem to regain lucidity and even go off and resume normal activities. Later on they very quickly go drowsy and lose into unconsciousness s the clot forms. It is a life-threatening event and the trephination could be life-saving.

Be bold!

I have used trephination in some of my western stories. I have had both my main protagonist have an operation, as in Redemption Trail published by Western Trail Blazers and in one of my Dr Marcus Quigley stories. It is tough surgery performed in life and death situations, so the operator has to be bold. Which of course, all of us as western writers have to be.

***

Some of Clay More's latest releases:

Redemption Trail published by Western Trail Blazer

- a novelette- novella

Sam Gibson used to be a lawman, until the day he made a terrible mistake that could never be taken back. Since then, he has alternated between wishing there were a way he could redeem himself and believing he deserved punishment.

He’s about to get both…

REDEMPTION TRAIL

And his collection of short stories about Doc Marcus Quigley is published by High Noon Press

Available at Amazon.com:

And his latest western novel Dry Gulch Revenge was published by Hale on 29th August.

%2B1880.jpg)