THE DOCTOR'S BAG

Keith Souter aka Clay More

Medicine and surgery have always advanced during times of war. Surgical techniques are developed to deal with the wounds and injuries that weaponry cause. And medical innovations are often also introduced on order to make scant resources stretch further. In the Doctor's Bag this month I am going to focus on a doctor who contributed to medicine and surgery both during and after the Civil War. His invention of the Chisolm inhaler was one of the most significant medical inventions of the 19th century.

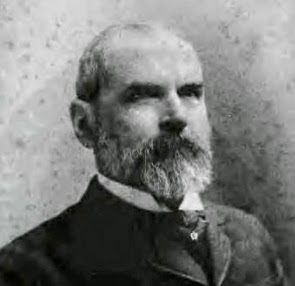

Dr Julian John Chisolm (1830-1903)

Julian John Chisolm, often referred to as john Julian Chisolm or as J.J. Chisolm was born in Charleston, South Carolina in 1830. He obtained his MD medical degree from the Medical College of South Carolina in 1850 then travelled to Europe to study medicine and surgery in Paris and London.

He returned to Charleston in 1860 and took up the post of Professor of Surgery at the Medical College. He kept the position throughout the War and in 1861 published the first edition of his textbook A Manual of Military Surgery for the Use of Surgeons in the Confederate States Army.

He was one of the few competent surgeons at the start of the War (it was the steepest of learning curves for surgeons on both sides), but his book gave detailed instructions. His experience was based on personal observations of many wounds treated in both civilian and military hospitals admitted form the battlefields of Europe. The book was updated twice during the War.

He also indicated his views on the practice of venesection (blood-letting) in chest wounds.

"Where the heart and pulse are both weak--a common

condition after severe wounds--in our experience the abstraction of blood will

occasion a complete prostration of strength, and may be fatal. There is no

reason for changing the plan of treatment already discussed in detail, for

combating inflammation following gunshot wounds, and which is equally

applicable to chest, wounds. Even when the lung is inflamed, we prefer the mild

antiphlogistic and expectant treatment to the spoliative. The large success in

the treatment of perforating chest wounds in the Confederate hospitals puts

forth, in a strong light, the powers of nature to heal all wounds when least

interfered with by meddlesome surgery. Absolute rest, cooling beverages,

moderate nourishment, avoiding over stimulation, with small doses of tartar

emetic, veratrum, or digitalis, the liberal use of opium, and attention to the

intestinal secretions, will be required in all cases, and in most will compose

the entire treatment."

During the war chloroform took over from ether as the anaesthetic of choice. It was administered by using a piece of cloth, which was fashioned into a cone, onto which the chloroform was administered. This was found to be wasteful, since much of the chloroform evaporated. Hence it was unscientifically and crudely given and could also affect anyone see in the enclosed space used as an operating theatre. In a field hospital that may have been a tent.

With the Union Naval blockade the supplies of chloroform were drastically reduced. Stimulated by that, and by the wasteful and hazardous way it was traditionally given he invented his inhaler. It consisted of a flattened cylinder, measuring 2.5 by one inch, with two tubes which could be inserted into the nostrils. The chloroform was dripped into a perforated disc onto a cloth inside the inhaler. It reduced the amount needed to a mere ten per cent.

Surgeon, Scientist and Medical Purveyor

On the September 20, 1861 he was appointed as Surgeon in the Confederate Army and set up a hospital in Manchester, Virginia. Then in November of that year he was ordered to set up a medical purveyor's office, which received and distributed medical supplies and surgical instruments to surgeons and doctors in the field.

The purveyors office was later moved to Columbia, where he established a laboratory. There he developed medicines that were also in scarce supply because of the Union Naval blockade. The drugs were made from indigenous plants

Members of the public were asked to help the war effort and grow plants:

In obedience to an order of the Surgeon General, I … request … ladies of the South to extend the sphere of their usefulness, by interesting themselves in the culture of the garden Poppy; by which they will administer to the relief of our sick and wounded soldiers and render essential service to our Confederacy. The seed of the Poppy should be planted in rich ground, and the largest pods or capsules selected for use. To obtain the gun, the pods or capsules – a few days after the (illegible), should be cut longitudinally through the skin. This would be done later in the afternoon, the hardened gum being scraped off in the morning by means of a dull knife, then wrapped up carefully, and should be sent to the nearest Purveyor. Persons having seed of the poppy, will be paid a liberal price for them at this office. R. Kidder Taylor, Surg. And Med. Purveyor, CS Army.

Dr Chisolm had in his laboratory 'a series of copper kettles for evaporating.' He recommended staffing other laboratories with chemists from Europe, skilled in extracting alkaloids from plants. In particular, he gave the example of finding a substitute for quinine, which was in extremely short supply and which was needed to treat malaria. The normal source of quinine was the cinchona trees, which do not grow in the south. A tincture could be made of willow, dogwood and poplar bark as a substitute.

With the ultimate Union advance in June 1865, Dr Chisolm turned over to a Union

officer 'all machinery, injured by fire formerly used at the Confederate

States laboratory & Distillery located at the Fair Grounds on the outskirts

of the town of Columbia.' This included about 80 pounds of gum opium and 340

ounces of morphine.

Professor or Eye and Ear Surgery

After the War, Dr Chisolm moved to the University of Maryland in Baltimore and accepted the chair of Eye and Ear Surgery created for him. Once in post he founded the Baltimore Eye and Ear Hospital and the Presbyterian Charity Eye, Ear and That Hospital. He is considered to be the founding father of American Ophthalmology.

He wrote over a hundred medical papers and continued to be innovative in his surgery and in his research. In 1888, for example, he grafted a rabbit cornea onto a human. He also made significant advances in cataract surgery.

Helen Keller, Charles Dickens and Alexander Graham Bell

Helen Keller (1880-1968), the famous American activist, author and lecturer had been taken to see Dr Chisolm as a child, after she had gone deaf and blind following a childhood illness. It is possible that the illness was scarlet fever or meningitis. He advised her to be seen by Alexander Graham Bell, who was working with deaf people at the time. His parents had both been deaf, which had led him to try to develop a range of hearing instruments for the deaf. As a result, in 1876, he had patented the first useable telephone!

Interestingly, Helen Keller's parents had been inspired after reading Charles Dickens American Notes, about his travels in America. In it he mentioned visiting the Perkins School in Boston,where he had been impressed at the work of Dr Stanley Howe, the director of the Perkins Institution for the Blind, with Laura Bridgman, who would become the first blind-deaf person in America to gain a significant education in English. It was Laura Bridgman who advised seeing Dr Chisolm.

Dr Chisolm had a stroke in 1894, from which he made a partial recovery. He died in 1903 in Petersburg, Virginia.

*******************************

Clay More's novel about Dr George Goodfellow is published in the West of the Big River series by Western Fictioneers.

Available at Amazon.com:

And his collection of short stories about Doc Marcus Quigley is published by High Noon Press

Available at Amazon.com:

And his latest western novel Dry Gulch Revenge was published by Hale on 29th August.