Kit Carson

Flash

back 151 years to February 1863.

At

that time Kit Carson was a bona fide American hero. It’s right there in Herman

Melville’s Moby Dick: frontiersman,

mountain man, Indian fighter. He was also a hero of the Mexican-American War,

“Father Kit” to his Ute and Apache Indians on his Agency, fictional hero-savior

to any number of innocent women and children in distress in the 19th

Century “Blood and Thunder” dime novels, and loving Taos father and husband to,

over time, three wives, two of whom were Cheyenne Indians.

John

M. Chivington was a Methodist Minister celebrated for his role in turning the

tide against the Texans in the Civil War Battle of Glorieta in New Mexico

Territory, and then helping the citizens of Denver City and the ranchers along

the south fork of the Platte River fend off raiding Cheyenne Indians.

On

the other hand, many of the Cheyenne warriors harassed farmers and settlers,

while the Navajo Indians---the Dine---were friendless throughout the West.

Severely and serially ill-treated by the Spaniards in the preceding centuries,

the Navajos evolved into a civilization that discriminated against no one in

robbing, pillaging, murdering, and enslaving women and children. The Dine

succeeded in the seemingly impossible: uniting Whites, New Mexicans, Pueblo

Indians, Cheyenne, Utes, Mexicans, and all manner of Apache tribes in their

hatred of marauding Navajo warriors. Even the Navajo headsmen, when confronted

with the opportunity to bring peace, admitted that it was beyond their power to

stop their young men from raiding. They essentially responded to attempts by

the U.S. Army to enlist their support with the 19th Century

equivalent of “Kids today!”

What

about today? The general view of the Navajo today is one of a venerable,

peaceful Native American culture. A spiritual nation inhabiting their reservation

on their native lands in northern Arizona. A people that, to this day, largely

view Kit Carson as a genocidal murderer of innocent Navajo. And the Cheyenne,

astonishingly only around 2,500 people at their peak while fighting the whites?

The Cheyenne are arguably viewed as one of the great nomadic tribes of the

Plains, begrudgingly held by their opponents as maybe the greatest cavalry

ever, and today as a positive force for Native American cultures.

And,

if asked to name great American frontiersman, very few Americans get to Kit

Carson’s name, even after mentioning Lewis and Clark, Davey Crockett, Buffalo Bill

Cody, and maybe Jim Bridger. And virtually nobody has anything good to say

about the despicable John Chivington.

What

happened during the intervening 150 years to bring about this 180-degree change?

My

first introduction to the legend of Kit Carson was by a young Navajo guide on a

private tour of Canyon de Chelly. He took me to a medium-high, cylindrical hill

covered with brush and small trees deep in the canyon and said, “That’s where

Kit Carson brought the Navajo women, children, and elderly and massacred them.”

Years later, a friend told me of his

tour of the Canyon and the story he’d

been told of the massacre at that same spot. But his guide’s version was that

the culprits were the Spaniards, centuries before Kit Carson. And then I read

Hampton Sides wonderful Blood and Thunder.

That book launched me into research into the history of the Southwest. A

passage in it inspired me to write my own novel, Where They Bury You, Sunstone Press, a murder mystery based on the

actual 1863 murder of Carson’s U.S. Marshal.

Six

or seven generations of Navajo oral history about the, in fact, horrible 1860’s

“Long Walk” to Bosque Redondo has left many, if not the majority, of living

Navajo believing that Carson was responsible.

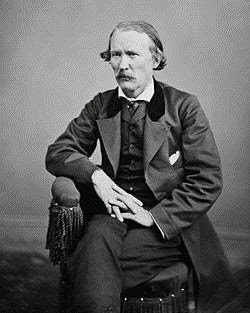

General James Henry Carleton

The actual

fact is that Bosque Redondo was the misguided vision and policy of one General

James Henry Carleton, head of the Union Army in the Territories. When the Civil

War battles ended in the New Mexico and Arizona Territories in 1862, the Navajo

and Mescalero Apaches continued raiding and killing, and, in the case of the

Navajo, enslaving the New Mexican people and tribes. Carleton decided the only answer

was to round them up and deport them to Bosque Redondo, a totally inappropriate

section of land along the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico.

Carson

objected to the policy as untenable and tried to retire to his family and his Ute

and Jicarilla Apache Agency. But Carleton insisted that the famous frontiersman

carry out his last military orders.

First,

Carson induced the Mescalero to surrender and delivered them to Bosque Redondo.

The

Navajo turned out to be a bigger challenge. They simply vanished into the

deserts and canyons of their homeland. Carson, frustrated by his inability to

find the Navajo and their previous refusals to stop raiding and killing the

other neighboring tribes and New Mexicans, implemented a scorched earth policy

throughout the Dine homeland. It took nine months, but the Navajo people began

trickling in and surrendering. Carson, objecting to the 9,000 person four

hundred mile walk without adequate provisions, returned home to Taos for

several months. He then insisted on being the Indian Agent at Bosque Redondo in

a failed attempt to help the Navajo adjust to their new home.

Carleton’s

Bosque Redondo was a colossal failure. The Mescalero just up and left one night

in 1865 to return to what continues to be their home near Ruidoso, New Mexico.

The Navajo negotiated their departure and walked the four hundred miles back

home in June 1868, one month after the 55 year old Carson died in Taos.

At

the time, General Carleton was blamed for the failure and, in 1878, returned to

his Texas home to die in relative obscurity. The Navajo, though, have never

stopped blaming Carson for their hardships and deaths. Today, the Navajo story

and memory of Carson’s culpability resonates better in the public American culture,

while the numerous Navajo depredations and Carleton’s miserable failure have

long faded into history. In contrast to modern New Mexicans, some modern Native

American tribes still do retain a very

negative cultural memory of the Navajo history.

Justifiable

or not, reaction to the Navajo oral tradition had caused Carson to lose his

chance to be remembered alongside Davy Crockett and Buffalo Bill Cody and Lewis

and Clark as a first string All-American legend.

John Chivington

Chivington,

for his part, until recently had been celebrated for over a century by

Coloradans for his part in defeating the Cheyenne at the Battle of Sand Creek.

That “battle” took place one hundred fifty years ago last month. Over the

recent decades, historians, Native Americans, and Chivington’s own family have

more accurately portrayed the “battle” as it in fact was, namely the massacre

of innocent women and children.

Black Kettle

How

Carson actually felt about the Indians is best expressed by Carson himself

about Chivington. The Cheyenne under Black Kettle had disarmed and relocated

their village at Chivington and Governor Evans’ direction. While their warriors

were out hunting, the truly despicable Methodist Minister and commander of the

Colorado Volunteers massacred and mutilated the defenseless elderly, women, and

children of the village. Carson was asked to testify at the resulting Congressional

inquiry. He testified:

“Jis to think of that dog Chivington and his dirty

hounds, up thar at Sand Creek. His men shot down squaws, and blew the brains

out of little innocent children. You call sich soldiers Christians, do ye? And

Indians savages? What der yer 'spose our Heavenly Father, who made both them

and us, thinks of these things?

“I tell you what, I don't like a hostile red skin any

more than you do. And when they are hostile, I've fought 'em, hard as any man.

But I never yet drew a bead on a squaw or papoose, and I despise the man who

would.”

It

is said that the winners write the history books. But it is often more

complicated than that. Respect and pride should, and does, go out to the

surviving, constructive cultures of both the Navajo and Cheyenne Indians.

Chivington is now properly remembered for the horrific person he was. The public

jury is still evolving on Kit Carson. The final chapter may not yet have been

written. We’ll see.

Carson

and Chivington figure prominently in my historical fiction novel, “Where They

Bury You,” 2013, Sunstone Press.

Chivington,

Black Kettle, and George Armstrong Custer carry the story in the sequel, “Chief

of Thieves,” following the survivors of the first novel from 1863 Colorado to

June 25, 1876 at the Little Bighorn. “Chief of Thieves,” Sunstone Press, is

coming out this winter.

I’m

not hiding, and can be found at: